Why neurodivergent learners struggle

Barriers that neurodivergent learners face, and how we can help them thrive

Why does my neurodivergent learner struggle so much with basic skills?

First, we have to understand what neurodivergence means. Literally, it means “different brain” or “different mental processes.” If you are a Trekkie, you might notice that it is often diversity that saves the day. Whenever some fate befalls the majority of the crew, it is the differences that allow select crew members to take action. If you are a history buff, you might notice that some of the world’s greatest inventions and art likely came from neurodivergent minds. Looking at you, Da Vinci.

Neurodivergent people have differing brain chemistry and differing brain structures. MRI studies have shown that different areas of the brain “light up” and light up in different ways when doing the same tasks or exposed to the same stimuli compared to “normal” brains.* Some of these differences are adaptive. Some are not. Some can be significant barriers to effective or efficient processing.

Next, we have to understand the societal constructs and institutions at play here. We live in a world built by and for neurotypical people. Expecting neurodivergent people to navigate it as effectively and efficiently as neurotypical people do is unreasonable.

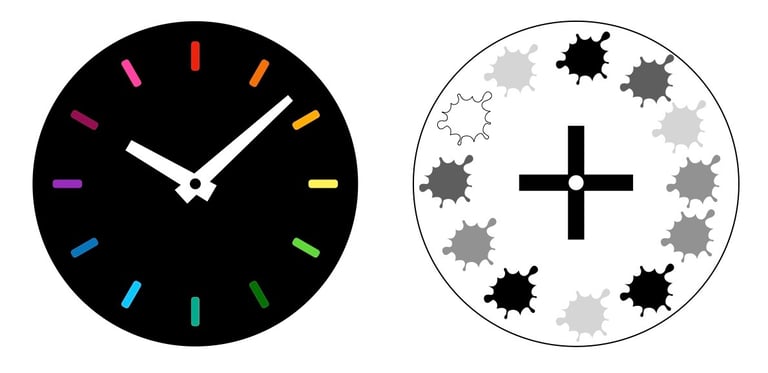

The clock neurotypical people have

The clock neurodivergent people have

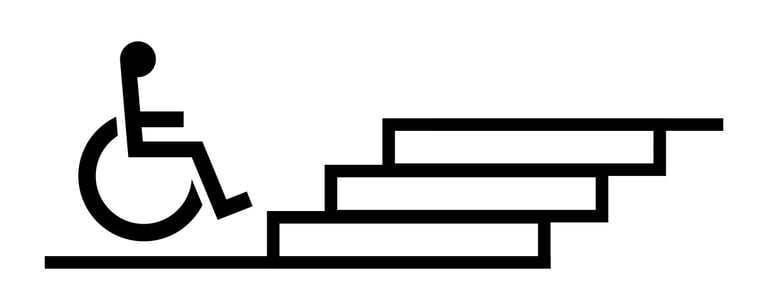

In this sense, neurodivergence, in and of itself, is not the problem. The problem is a society that does not accommodate neurodivergence. Someone with limited mobility is not hindered by their wheelchair. Their wheelchair is a necessary tool that allows them to access and engage with a much larger percentage of the world than they would be able to without it. The barrier is a lack of ramps and elevators. Unfortunately, you and I do not have the ability to go into every public space and demand ramps and elevators be added. Believe me, I would if I could.

We do have the ability to make a substantial difference in executive functioning skills and accommodations at home. We may or may not have the ability to enact accommodations at schools or workplaces.

I remember talking with an acquaintance when an alarm on my phone went off, reminding me to pick up my child from school.

“You need an alarm to remind you that you have a child at school?” my acquaintance scoffed. “How do you forget your child!?”

“I don’t forget my child, but I do lose track of time easily,” I mumbled, embarrassed. “This is just a safeguard to ensure I am on time.”

I got embarrassed easily back then. I wasn’t always the confident self-advocate I am today.*

What does this interaction say about the two of us? It says I had a barrier to time management and found a workaround. Yay me. It says my acquaintance struggles to know what is and is not their business and is arbitrarily judgmental. Which traits seem beneficial and which traits seem problematic?

How do we make a substantial difference? By employing key strategies that account for the strengths and accommodate the challenges of neurodiverse people.

Teaching methods must be clear and yet creative.

Neurotypical people pick up executive function skills seemingly effortlessly. Neurodivergent people need to be explicitly taught using methods that result in meaningful learning of applicable knowledge. I have not met a neurodivergent person yet who responds well to the typical “drill and kill” methods of repetition and memorization used with rote skills such as math facts or spelling.

The ability to adapt and apply acquired skills in novel ways must be nurtured.

Neurodivergent people may struggle with taking skills in one sphere and using them with tasks outside that sphere. Explicit skill instruction alone is not enough. They need to be taught to recognize their strengths and actively encouraged to think about how those strengths can be applied elsewhere. They may not see, for example, how a talent for video games indicates strengths in strategic planning, prioritization, and perseverance. Pointing it out may give them a brief emotional boost, but it does not tell them how to transfer those skills into the real world. If we can demonstrate how some tasks can be tackled in the way one tackles a quest, we have just made those tasks more achievable.

Fostering confidence is therefore not just a requirement but a prerequisite.

Many neurodivergent people, especially if they are either recently diagnosed or undiagnosed, have been on the receiving end of judgment and inaccurate labels such as lazy,* often for years. When those mindsets become internalized, recognizing strengths can feel impossible. They undoubtedly have strengths, but those strengths might be buried under years of accumulated criticism.

Modifying the environment and utilizing appropriate accommodations must be encouraged.

Spaces for neurodivergent people need to be designed thoughtfully. Simple changes can make a big difference.

Keeping my socks in my nightstand drawer means I don’t start my day with my feet coming into immediate contact with a cold floor. It may not seem like much, but it is definitely easier to coax myself out of bed if my feet are warm and cozy.

Having a drop spot/launch pad in a convenient location makes it easier to keep track of important belongings. This can be as simple as a key hook or as detailed as a mud room stocked with shoes, umbrellas, reusable shopping bags, grab-and-go snacks, towels, and a place to store a backpack, briefcase, diaper bag, etc., for each household member.

I have a detached garage. My home is also short on storage space. This means that bulk purchases get stored in the garage. I maintain a stack of cards with pictures of important items in my launchpad. Putting a card with my keys means the next time I go to the garage, I should grab that item. This saves me the inconvenience of stopping what I am doing to run to the garage when I notice something is running low. It gives me a quick way to note the needed item and move on, so I am not using valuable mental energy holding on to this task, or risking forgetting about it entirely. I am a visual person. Someone more auditory may prefer to verbally tell Siri, Alexa, etc., to set a reminder alert. The method is not important. What is important is to build whatever systems you need into your daily life to track items, tasks, etc.

Different accommodations will work for different people. You may need to play around with your environment several times before you find the methods that work for your family.

Once explained, it seems obvious that facilitating the development of executive function skills can have a profound effect on achievement. This means that caregivers of neurodivergent learners have every reason to be hopeful.

This is something we can do.

Footnotes:

1 I am not even going to speculate as to what a “normal” brain is.

2 Like a lot of caregivers, I am better at advocating for the learners in my life than myself. It has taken decades to become as comfortable in my own skin as I have always encouraged my learners to be from the start. You are not alone if you struggle with advocating for yourself.

3 See my post “Lazy is a myth”